A bright light has been shed on what has been a 20-plus-year effort to bring a new amenity to the baseball field at Tracy Area High School.

Last month, District No. 2904 School Board member Jay Fultz presented an option the district could pursue to install lights at the field. After hearing a breakdown of a lighting proposal from Fultz, the board tabled the discussion until this month’s meeting, where a second option was brought to the board.

The board on Monday passed a motion to contract with Sports Lighting Authority to gather specs on lights, meaning the question is now not whether or not to move ahead with the project, but to buy new or used lights.

“They’re advisors, they go out and get bids for you and do all the specs,” Tracy Area High School Activities Director Bill Tauer said.

The cost to the district for Sports Lighting Authority’s services to oversee the project is $12,230, no matter if the district goes used or new. If the district chooses to use the company just for bids and specs, that cost would be $6,115. Used fixtures would include High-Intensity Discharge (HID) lighting. The life expectancy of used HID fixtures is between 10-12 years.

Tauer said Craig Gallop of Sports Lighting Authority recommended going new if it fits in the budget; monies from the General Fund would be used to pay for either a new or used lighting system. Fultz made the motion to hire Sports Lighting Authority and later amended his motion to include collecting bids for either a new and/or used option.

The first option brought to the board in August was to purchase eight 2- to 3-year old, metal halide fixtures on 70-foot galvanized poles; two poles have four lights, four have six lights, one has eight lights and one has 10. The Musco lights are currently standing in Winthrop, and the asking price is $10,000 per pole. The district can pay another $70,000 to the owner of the lights to take them down, transport them to Tracy, auger out and pour new bases and reset the poles. The underground electrical work would be an additional cost.

The TMB baseball team plays many of its games in Milroy because of the lack of lighting in Tracy. Tauer estimated between high school, Legion and youth ball, the lights would be used about 25 times for roughly two hours for each event.

“It boils down to how much more are you actually going to spend for new compared to used,” TAPS Supt. Chad Anderson said. “Are you better just going brand new? Maybe. We definitely like the idea of having a company do it and do it right.”

In other news from Monday …

• The board accepted the following donations: $50 anonymous donation for a TAHS scholarship; Bruce Berg (trombone, clarinet and oboe); Aaron Frisvold (barbells and bumper plates); $3,000 and $3,200 from Apex Clean Energy (softball complex and FFA trap team, respectively); $490 from the PTC (first-grade field trip); and $190 from the PTC for the kindergarten field trip.

• The board approved to certify the MDE Levy Limitation and Certification for 2025 Payable in 2026 a the maximum level of funding allowed by State law.

• The board approved the hiring of Lindsey Grunden as JH volleyball coach for 2025 and the resignation of Alex Greenway as assistant track coach.

Frazier never graduated from high school. He lived on his own in Tracy in an apartment complex after being emancipated at age 16. He would eventually find his way to the Big Brother program in Tracy; that’s where he found Gale Otto and his former wife, Jan Arvizu. Gale and Jan took Frazier in for what proved to be his longest stay in any home. Other foster home experiences, Frazier said, would be pit stops that lasted anywhere from two to four months.

That’s a tough road to hoe for an already emotionally-damaged teen.

“I had already been in a foster home in Utah when I was in the first grade, so it had already been a part of my life,” he said. “Foster home, to my mom, to a foster home, to my mom. You can’t develop any friendships, you have trust issues. I wasn’t being careful mentally; I just was … angry because I had no control, just going where everybody told me to go.”

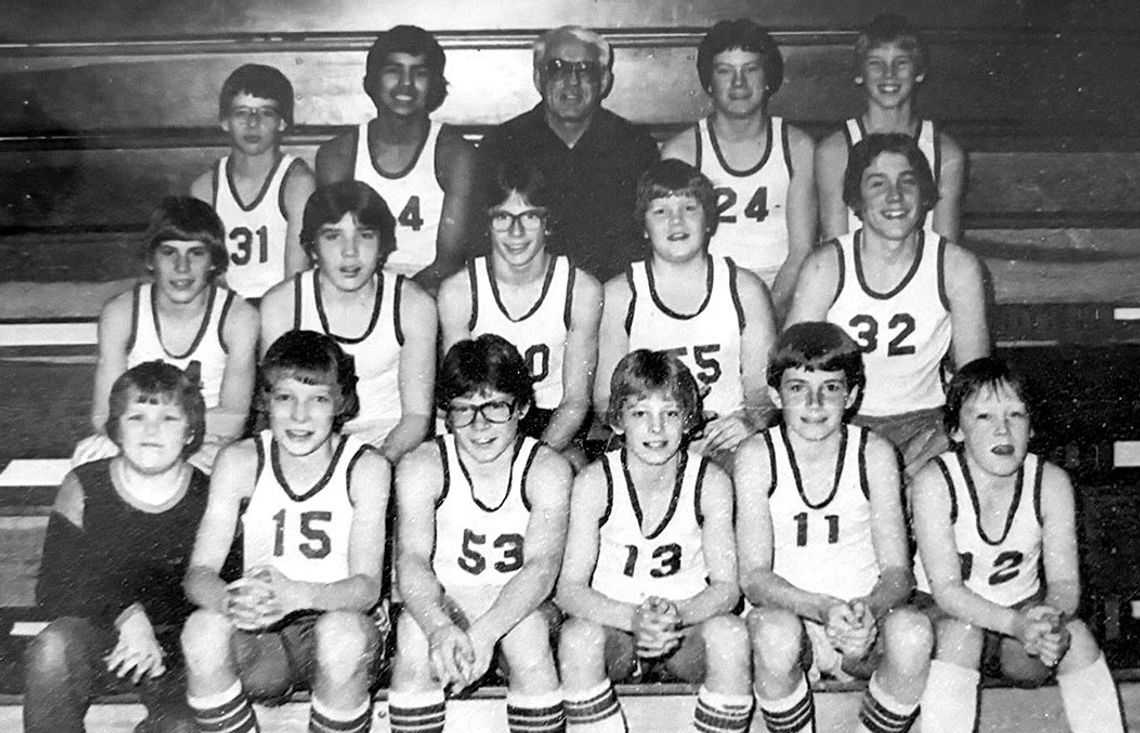

Frazier, who in retrospect, calls high school sports his only shot at pure expression of who he was, said there was never a time in his young life where he felt he could settle down, no matter the community he might have been in. Having fallen into a pattern of moving from foster home to foster home, his thought process became one of “what’s next?” But this wasn’t him looking to the future with wide-eyed optimism; instead it was a teenager looking ahead to the unknown while slowly but surely losing a part of his youth that other kids might take for granted.

“I would get a phone call at school … ‘No need to dress today for practice,’” he said. “It was hard. I was always the new guy at every school, I got in fights …” Losing out on the chance at any kind of consistency growing up wasn’t just about his home life. Bit by bit, he also lost the opportunity to continue to develop as a student-athlete in high school. And his past discretions didn’t just set him back at Minneota.

“(The Vikings) saw me as a kid that can play,” he said. “I had soft hands, I could catch. I was offered scholarships for football, but word got out that I was a troubled kid. I know for a fact I could’ve played at a higher level.”

As if growing up in foster homes wasn’t hard enough, being a Native American only made Frazier’s youthful journey even more bumpy. He said foster care for his people in that era didn’t allow native-born minors to live in a non-native home for more than six months under the Indian Child Welfare Act.

“I was being shuffled around because of the law,” he said. “And things didn’t pan out for me. It’s strength of communication that keeps a family together, and that wasn’t given to me. Nothing was given to me about how to be a good man.”

Coming back to Minneota on Sept. 6 to be honored as part of that ‘85 team — it was the first time he had set foot on K.P. Kompelien Field since that snowy November day — turned out to be a cathartic experience for Frazier, now 57. He said it allowed him heal. Today, well after 12 trips to treatment facilities, his substance abuse problems are far behind him. It wasn’t until just before he turned 40 that Frazier — at that time living in a Salvation Army adult rehab center in Omaha, NE, — realized he had to make a substantial change.

“I was sitting there, almost 40, in a homeless shelter thinking, ‘When did this become acceptable?’” he said. “‘When did this become OK for a man?” That was it, and I started changing. I found a spiritual path that I never had.”

Frazier has been sober for more than 15 years.

“The final (visit to a treatment center) it finally set in with me because I wanted a change,” he said. “I started to look for things that could change me; I was tired of doing it my way — it wasn’t working. I went to a place where I had a chance to talk about my Creator, and spiritual development and spiritual connection.”

After successful recovery, Frazier went back to his roots and discovered cultural practices. As an American Indian, he now conducts traditional native Dakota value ceremonies with the Wellbriety Movement in Montevideo, an organization that provides culturally-based healing for Indigenous people. Its mission is to disseminate culturally-based principles, values, and teachings to support healthy community development and servant leadership, and to support healing from alcohol, substance abuse, co-occurring disorders, and intergenerational trauma. Frazier is also signed up for Native American peer education for recovery. His niché as a grown man is helping others heal from their pains of the past. In doing so, Frazier has been able to reconcile with his own.

“I found some men that practice recovery through Native culture,” he said. “I sing, I’ve helped set up several teepees this year. I’ve done teepee teachings, sweat lodge teachings.” Frazier, who was born in Nebraska, said his past has been a big part of making him better appreciate his present, and his future. To this day, he calls Tracy home, even though the time spent there represents only a small fraction of his life. “I look at Gale as a father figure,” he said. “He set the tone for what a father should look like. I had an absentee father, I had been in six foster homes before I met Gale. And to this day, me and Jan still talk, we still communicate, we still share.”

The rough road Frazier traveled is far behind him now, but with 40 years of shame and guilt a thing of the past, there is one thing that still bothers him to this day.

Standing about 30 yards from the end zone where he caught that touchdown pass against Becker some 40 years ago, he said, “I still haven’t received my Minneota varsity letter yet!”

Frazier then laughed the kind of child-like laugh that, for the better part of his life, just wasn’t present. A couple Saturdays ago, this once-troubled boy could only smile.

‘

I was sitting there, almost 40, in a homeless shelter thinking, ‘When did this become acceptable? When did this become OK for a man?’ That was it, and I started changing. I found a spiritual path that I never had.

— JEROME FRAZIER